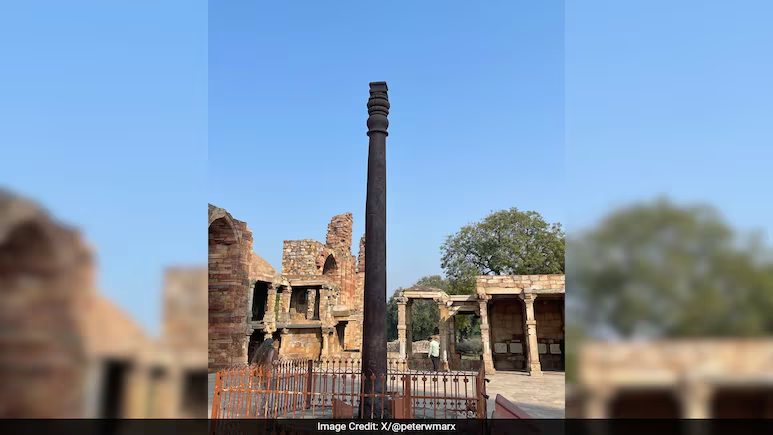

Many scientists are interested in a UNESCO-listed iron pillar in New Delhi that is over 1,600 years old and still rust-free. The iron pillar is over 7 metres tall and weighs around six tonnes, making it older than the complex it stands in.

Despite being erected in the early 400s AD, the iron pillar in Mathura has survived without any signs of corrosion, records the Archaeological Survey of India. Iron and some iron alloy products, when exposed to moisture, often develop rust and oxidize over time, unless they are first protected by suitable paint.

Nothing stops the iron pillar from rusting, so why hasn’t it happened?

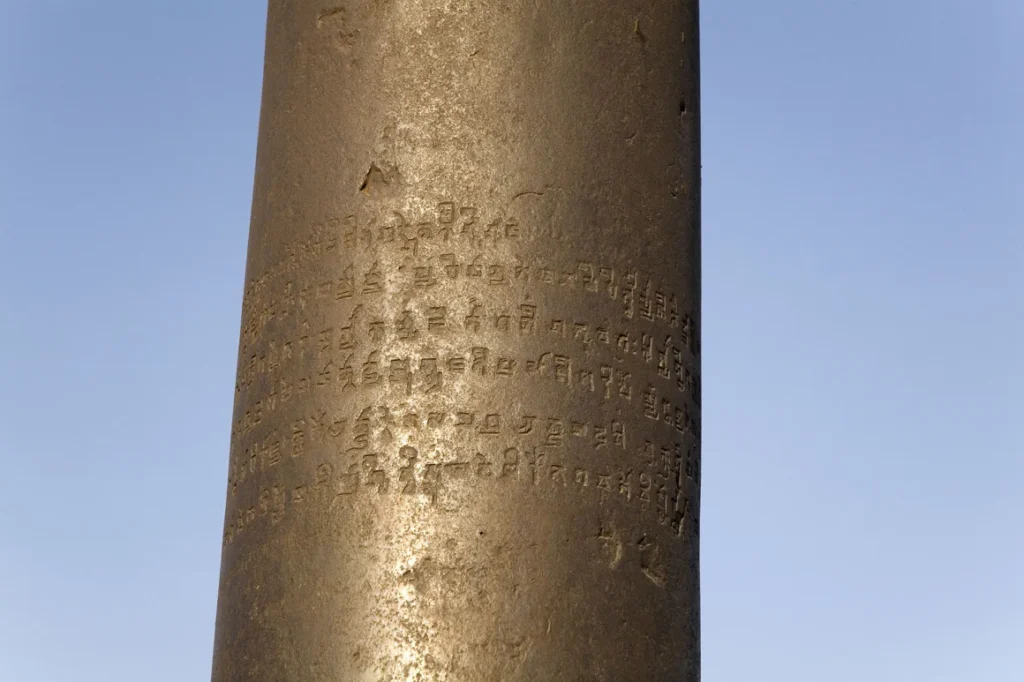

From 1912, scientists worldwide were interested in solving the mystery. Murray Thompson and Percy, working from Roorkee Engineering College and the School of Mines, used chemical testing to determine that the bulk of the construction was wrought iron, with a specific gravity of 7.66.

Only in 2003 did researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT)-Kanpur discover the true engineering secret that allows the structure to stand.

According to the study, the pillar consists mainly of wrought iron and contains about one per cent phosphorus (approximately). There was also a layer of misawite, made from iron, oxygen and hydrogen, forming on the pillar’s surface.

To conclude, the small and heterogeneous features within the Delhi pillar iron do not change the forming process of the protective passive film. According to the study, what gives Delhi pillar iron great resistance to corrosion is its high phosphorus content.

The pillar was made differently from today’s irons because ancient craftsmen didn’t have sulfur or magnesium and used the method of forge-welding. When using this technique, the iron is heated and beaten, to preserve its high phosphorus content, this form of making is not typically done these days.

Report author R Balasubramaniam, who is an archeo-metallurgist, stated that using an unusual technique made the pillar very resilient and reliable.

How has it defied corrosion for so long?

Most often, the rust that develops from oxidation on iron and iron alloy structures in outside environments is prevented by painting them, as seen on the Eiffel Tower. In 1912, people began studying the iron pillar in Delhi, trying to explain why it had not corroded.

The secret was revealed in 2003 by researchers at the IIT in Kanpur, who reported their discovery in the journal Current Science.

They noticed that the pillar, mostly metal, has a phosphorus content of about 1%, but little or no sulfur and magnesium like typical iron nowadays. Craftsmen from ancient times practiced a method known as forge-welding.

As a result, they melted and beat the iron to shape it with high phosphorus which is a technique seldom found nowadays.

According to the archeo-metallurgist R. Balasubramaniam, the unusual building technique kept the pillar strong.

A layer of “misawite” was discovered on the pillar’s surface, according to the team. High phosphorus in the iron and no lime cause this layer to be formed catalytically which helps strengthen the pillar even more.

He praised the skills of the metallurgists, saying the pillar was proof of India’s ancient metalworking abilities.

One example from long ago shows that this monument stands strong after a cannonball accidentally hit it, proving that Los Pilares is extremely durable.

Both the National Metallurgical Laboratory and the Indian Institute of Metals now use the pillar as their emblem.

Myths and legends surround pillar’s origin

Besides the interesting story of the Iron Pillar’s making, its place of origin remains unknown. A widely accepted story says that it began in the Gupta Empire, especially under the rule of Chandragupta II who was also called Vikramaditya during the 4th and 5th centuries.

According to the folktale, the pillar was built inside the Varah Temple of Udayagiri Caves near Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh to honor Lord Vishnu. Some say the site once featured a statue of Garuda, the mythical eagle portrayed as Vishnu’s mount, at the top, but it can no longer be seen.

According to heritage specialist and teacher Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, rather than being included among royal clothes, Jyotish Ratnavali was likely bought by Varāhamihira, an important astronomer in King Vikramaditya’s court.

In the ‘Surya Siddhanta,’ one of his books, he set out methods for figuring out stars and eclipses and people think he used a tall pillar for his calculations, Vikramjit explains.

As a result, when Brahmagupta went from Vidisha to Mihirapuri (now Mehrauli) to build an observatory, it seems possible that he moved the pillar to keep using it in his research and calculations.

Some ancient records mention Raja Anangpal of the Tomar dynasty and well as Iltutmish and Qutbuddin Aibek, as responsible for moving the pillar to the Qutb complex.

The arts have acknowledged it too. In his epic poem “Prithviraj Raso,” Chand Bardai, a member of the king’s court, refers to the Iron Pillar as a vital object.

“Bardai in Raso says that the Iron Pillar hangs the Earth from Sheshnag’s hind foot, the serpent king of Hindu mythology, according to Vikramjit.

Raso shares that Raja Anangpal ignored Brahmin advice and tried to remove the nail even though he might suffer. Once we moved the stone and found the red base believed to be Sheshnag’s blood, people everywhere were terrified and thought the planet would die. The reinstallation was done right away by Anangpal, but the security was not strong and it came loose. As a result, Bardai argues that the loose sand inspired the Hindi word ‘dhilli’ and that lead to people calling Delhi ‘Dilli’ from then on.

Cultural significance and preservation efforts

Some tales say that if you face the pillar, press your arms around it, ensuring your fingers overlap, your wish will be granted – giving the pillar an extra meaning beside its significance in history.

The ASI has installed a fence around the pillar to help protect it from people.

Pragya Nagar, who works in conservation, wonders how the pillar survived unchanged while its background was changed many times.

“If we analyze the techniques involved in making the pillar from another angle, we could begin to use them to develop sustainable alternatives to existing materials, because producing metals can cause pollution,” she says.

Looking at history locally means understanding the values and skills that were once common among the people. The use of this method could lead to a more sustainable future.

For more updates follow: Latest News on NEWZZY