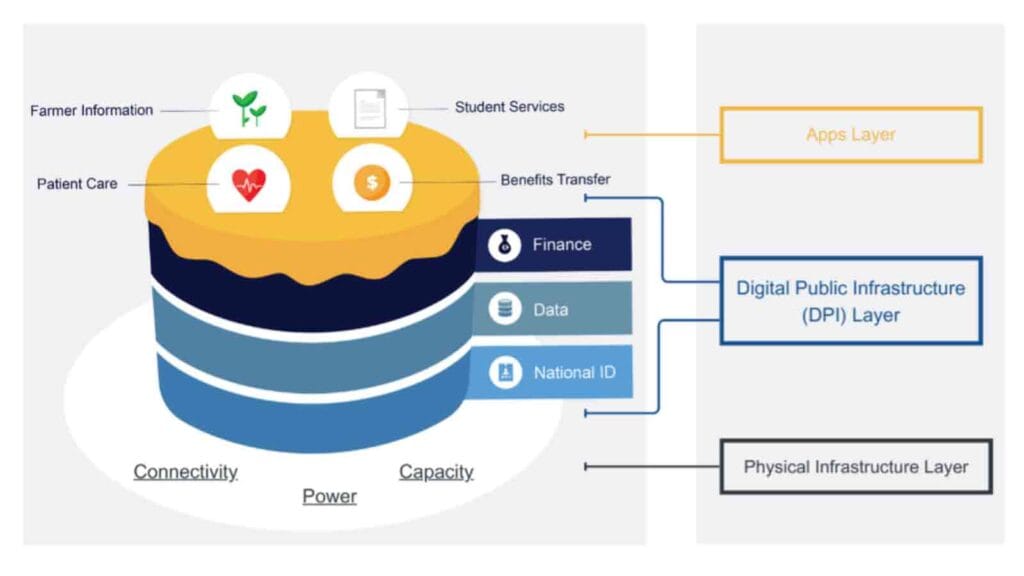

It is an invisible revolution that is fueled by Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), which is happening in the world. It is not merely a technological improvement but a paradigm shift in how countries organize their digital economy, provide people with services, and create geopolitical power. DPI, the digital equivalent of roads and power grids, is an open, interoperable and consent-based architectural stack built as a public good, which spearheads economic leapfrog in the Global South and requires the North to rethink governance.

Read About: Decentralized Identity in Banking – The Future of Fraud Prevention | 2025 Report

Table of Contents

What is Digital Public Infrastructure?

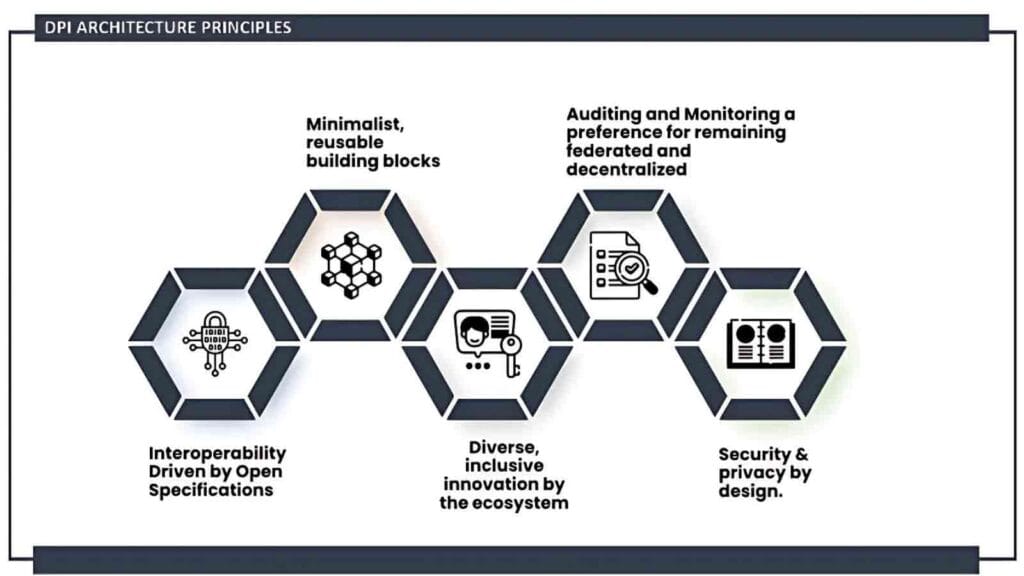

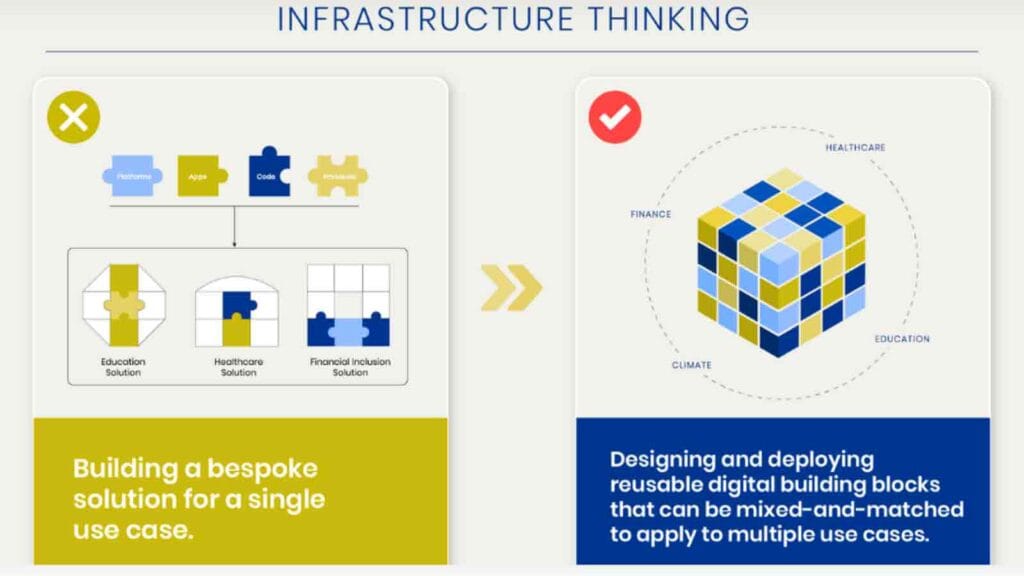

Digital Public Infrastructure entails the underlying, public digital systems, including identity, payments and data exchange, that can support core services on a societal level. In case the Big Tech platforms represent the walled gardens of the online sphere, DPI represents the public square: open, community-oriented and aimed at universal access. It has been successful because of its modular architecture that reduces the entry barrier of innovators.

Global Digital Public Infrastructure Case Studies

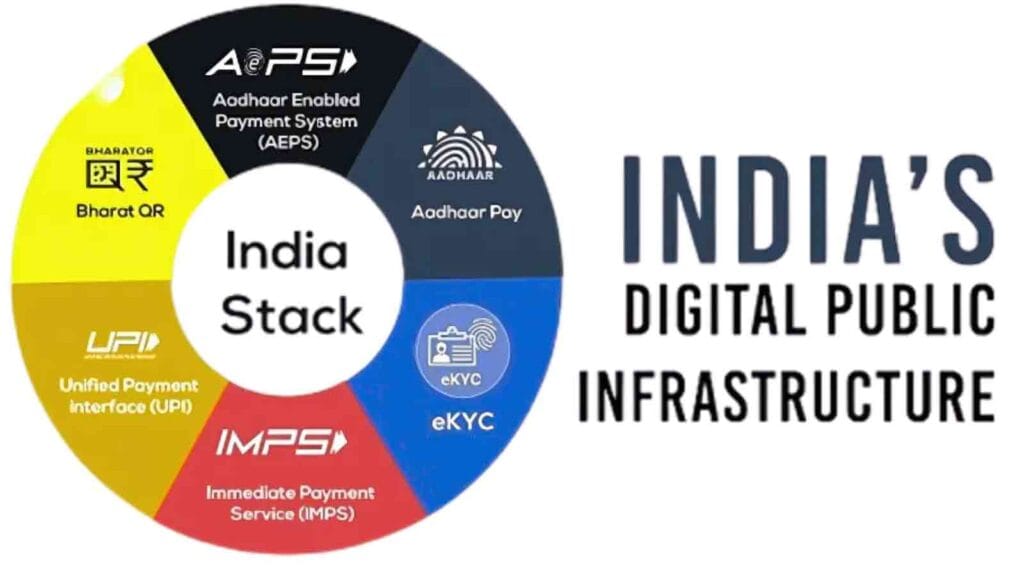

India: How to climb in Inclusion Open APIs: The most referred model of DPI is the India Stack. It has been successful due to the concept of the presenceless, paperless and cashless services.

The Scale of UPI: The sheer amount of transaction that UPI deals with demonstrate that it is the de-facto national digital currency that facilitates transactions between large retailers and street vendors at a very low cost.

Account Aggregator (AA): This Data Exchange Layer is newer, and it enables individuals to share their financial data with trusted parties (such as banks to take out loans) safely, which may open the door to enormous retail credit to the previously unbanked, and an Open Credit ecosystem (OCEN).

Estonia: Independence by Interoperability: The DPI of Estonia is an example of the way a developed country may become digital sovereign and effective.

X-Road: The data exchange network is distributed over cryptographic hashing and logging, which is sometimes called blockchain-like technology, to make all data queries auditable and unchangeable. The citizens have the foundation of this architecture since they are able to monitor the access of their data and when they accessed their Data Tracker.

e-Residency: This project is an extension of the DPI to non-citizens whereby they can set up and operate an EU company entirely online demonstrating DPI as an instrument of economic statecraft.

Brazil: Rapid with Regulatory Requirement: The success of the Pix system of instant payment in Brazil reflects the strength of a unified payment utility that is supported by the state. Introduced by the Central Bank its compulsory introduction to all major financial institutions guaranteed a universal coverage practically overnight.

Speed and Cost: The process is free and near instantaneous to individuals, and it replaces expensive legacy wire transfers, and minimizes the use of cash, formalizing parts of the economy.

Financial Inclusion: Pix has brought millions of formerly unbanked or underbanked people into the formal financial system, demonstrating that a well-designed DPI can create massive financial inclusion quickly and in even late-bloomer economies.

India Stack | How does India’s UPI system work?

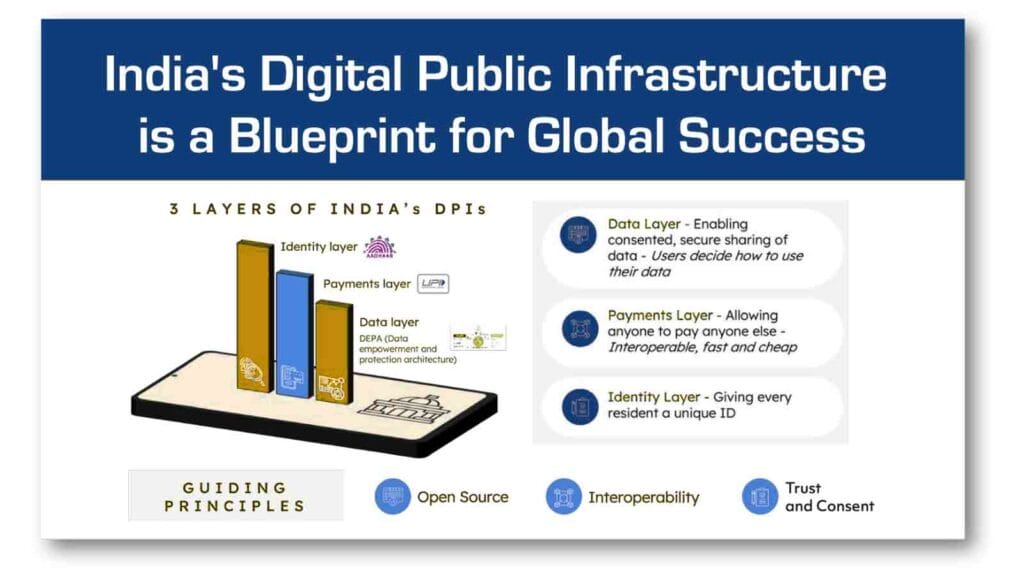

The most successful and scalable example has been considered as the suite of Digital Public Infrastructure in India which is commonly referred to as India Stack. It proved that strong, open, and interoperable digital systems were able to bring significant socioeconomic transformation in the country of more than a billion people.

Indian model is a very interesting case study of pole-vaulting development, which has made it in less than ten years of its development than half a century using conventional methods.

Transformative Impact of Digital Public Infrastructure

India Stack as an integrated approach has brought significant, quantifiable outcomes:

- Financial Inclusion: The proportion of financial inclusion citizens increased exponentially, about 20 to more than 80 percent of the population in ten years. This fast addition was made possible through linking bank accounts to Aadhaar identities (through Jandhan Yojana) and mobile based transactions through UPI.

- Less Leakages: Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT) through DPI has also ensured that government subsidies and welfare payments are directly deposit to the bank accounts of the target beneficiaries. This has saved the government about 41 billion dollars in form of ghost beneficiaries and bureaucratic middlemen.

- Innovation Ecosystem: The open source of UPI and Aadhaar enabled thousands of partner fintech firms to develop creative services on top of the DPI, creating a huge tsunami of economic activity.

The strength of DPI poses similar threats that have to be curbed through good governments and laws.

Watching and The Loss of Privacy in Digital Public Infrastructure

The main debate is the possibility of the creep of functions so that a system that was created with a well-intentioned aim (e.g. identity check) can be used to perform surveillance or control (e.g. social scoring). The state may develop a single point of knowledge by collecting identity and transaction data which is a threat to civil liberties even under privacy-by-design. Marginalized groups who do not have access to the digital world still face risks of exclusion and the idea of digital by default can be exclusionary in nature unless it is accompanied by successful, assisted access points.

Systemic Security Risks

The most important digital asset of a country is its DPI. Even an effective cyberattack would bring vital services to their knees–welfare checks to police logs. This provides a federated, decentralized security model and hence the reason systems such as X-Road log but do not store centralized information. Security should be founded on decentralization and transparency and not on obfuscation.

The Global DPI Race: Geopolitics and Models of Influence

DPI has become a severe instrument of soft power and geoeconomic control, in which a world race on digital standards is set.

This is the competition in international standards-setting organizations such as the UN and the G20 where the principles of DPI are being discussed. When India exports its DPI model it does not sell hardware, it sells a philosophy of governance and that philosophy is one that embraces inclusion and competition based on the public utility.

Governance and lacking Trust

Digital Exclusion Risk: DPI could find itself a weapon of systemic difference with marginalized communities reluctant or incapable of utilizing government-led digital applications because of the experience of political instability, trust, or insufficient digital skills.

Siloed Systems and Oligarchic Control: Unlike the greenfield approach in India, in many developing countries, the high costs and non-interoperable platform of oligopolies (local or international Big Tech) inhibits the quality of the DPI as a public good.

Interoperability and Local Situation

Going Direct to the Local Context: Most historic digitization had not been successful due to implementing solutions off the shelf that overlooked the values and capabilities of local governance, the regulatory environment, and the cultural norms themselves. DPI needs to be placed within the structures of governing and digital systems within a nation to guarantee continuity and adoption, and not the algorithmic colonization of interests by foreign entities.

The Dark Side of Digital Public Infrastructure

Although DPI is celebrated as a process of inclusion and efficiency, the aspects of its nature such as large-scale, centralization, and a strong dependence exacerbate some fundamental ethical, social, and security risks. Such scandals require deliberation and sound governance to safeguard the population to benefit through the use of digital infrastructure without violating the basic rights.

Monitoring Issues and Data Protection

The combination of identity and payments with the data exchange in DPI forms a single and complete digital portrait of each citizen, which is the ultimate instrument of not only governance but also control.

The Single Pane of Glass: Connecting the biometric identity (Aadhaar), transaction history (UPI), and the health/financial data (Account Aggregator) of a person can enable the state or a malicious attacker to make an almost indestructible and comprehensive life-log.

Mission Creep: The most serious threat is that welfare delivery or financial inclusion system will be used in mass surveillance, political targeting or social control. Despite the notion of privacy-by-design, such as virtual IDs, the presence of a central database is an issue of concern because of government control over it and a chilling effect on citizen behaviour.

Exposure to Insider Abuse: A centralized system that is secure by law is prone to abuse by insiders, security breaches or administrative mistakes that result in the open disclosure or misuse of highly sensitive personal information.

Marginalized Community Exclusion Hazards

Ironically, when infrastructure is created with everyone in mind, it might turn out to become an instrument of digital exclusion when the access to basic services becomes conditional upon DPI.

The Digital Divide: There are an estimated 850 million people in the world who do not officially have a single ID and millions more who are not literate, connected or have devices to utilize DPI. By conditioning welfare, food rations, or pensions on a digital identity or a biometric authentication, this essentially removes the neediest who ultimately are rejected in the verification, a phenomenon called “exclusion errors.”

Biometric Inaccuracy: Biometric authentication (such as fingerprint or iris scans) may be inaccurate on the elderly, manual workers, and individuals with some disabilities, resulting in repeated failures and denials of service.

Forced Digitalization: Marginalized populations are not always provided with an option that is not digital, so they must migrate to a medium of technology they might not trust, understand, or consistently access.

Single points of failure and vulnerability to security

It is also the greatest strength of DPI and its main security vulnerability, as it is quite interconnected and systemic. DPIs are a single point of failure (SPOF) of a society in general.

Systemic Risk: In the event of a disastrous failure of the central identity database, or the central payment switch, (either by a cyberattack, a critical bug, or a physical disaster) the core national functions would be crippled, with an inability to make payments, verify identities, and render essential government services.

High-Value Target: DPIs are the highest-value targets of nation-state actors, organized crime, and terrorists, because by compromising them there is the highest strategic and economic effect.

Vendor Concentration: The underlying technology is concentrated in several specialized international vendors or cloud providers and introduces a hidden SPOF, risk is a concentration point across multiple national systems.

Digital Colonization: Debate Who sets these standards?

Improved Digital Sovereignty and Control Digital sovereignty and control have become controversial due to the rapid push to adopt DPI, championed by global institutions and financed by international aid.

Data and Value Extraction: Critics note that DPI has the potential to become a process of so-called digital colonialism, with strong forces (be it developed countries or major multinational tech companies) shaping the construction of national systems to enable the extraction of national data to fuel their own global AI models and surveillance capitalism, with little or no input to the citizens who provided that data.

Importation of Foreign Logics: The importation of DPI structures created in the Global North/West or by particular leading nations may be an imposition of foreign technical, governance and commercial standards that erode local knowledge and sovereignty and establish a long-term technological dependency.

Conditionality: When the international financial institutions enforce the concept of DPI on a nation accessing credit or development funds, then this restricts the capacity of a country to make systems that are indeed specific to its cultural norms and values.

The Universal DPI Safeguards Framework

Introduced by the UN, this multi-stakeholder framework is an essential move towards having a world standard on responsible implementation and this aims at:

- Protecting the Individual: Privacy by Design, User Control (data sharing by consent), and Non-discrimination (non-discriminatory access).

- Protections to Society: Transparency, Accountability and making sure that DPI observes human rights and the rule of law.

- Techno-Legal Governance: According to this system, instead of issuing sluggish, general legislation, regulators can enforce policy through establishment of technical standards and protocols (governing the APIs), which makes more agile oversight possible.

Open Digital Public Goods (DPGs) should be encouraged

Creation and dissemination of Digital Public Goods Open-source software, open standards, and open data which meet privacy and security best practices should receive the emphasis of the international community. Examples of this include platforms such as the Modular Open Source Identity Platform (MOSIP), where nations can implement fundamental ID systems, and maintain full local control and ownership, saving dependence on one vendor.

The Future of Digital Public Infrastructure

The second frontier of DPI includes data layers that are focused on addressing issues that are global.

The AI-DPI Convergence

This is because the AI and DPI will spur a transition between reactive and proactive government. DPI offers the essential foundational, clean and consented datasets that are necessary to train more inclusive and less-biased AI models.

- Active Service Delivery: Systems will rely on DPI data to circumvent needs, e.g. an AI agent, or Kratt, might automatically process a welfare benefit increase or even proactively identify a lapsing license, simplifying bureaucracy.

- Language Inclusion: Multilingualism Multilingual populations can access government services via AI-based translation layers, like the Bhashini in India, which are based on DPI, and overcome significant language barriers in real time.

Carbon Accounting and U.S. climate DPI

The process of climate change requires a highly fidelity, auditory system of following the emissions and credits. This digital infrastructure would be offered by climate DPI:

- Open and Verifiable Carbon Ledgers: The creation of a trusted, interoperable layer of data interchange of all Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions data. This goes beyond opaque corporation reporting to cross entity carbon accounting where each and every emission is measured and assigned.

- Green Finance: This DPI would allow the transparent global carbon market where green credits and sustainable assets could be traced and verified opening the doors to performance-based climate finance.

Health DPI and Interoperability around the world

Health DPI is important to the future resilience of the public health. This includes designing secure and person-centric data layers of the medical records that can be viewed by authenticated providers with patient permission. The last phase of DPI is global interoperability, by establishing a network of national DPIs that enables the free flow of data across national boundaries to facilitate trade, health and travel, but without infringing a citizen right to digital self-determination. DPI is therefore not a system but the ultimate democratizer of the digital economy.