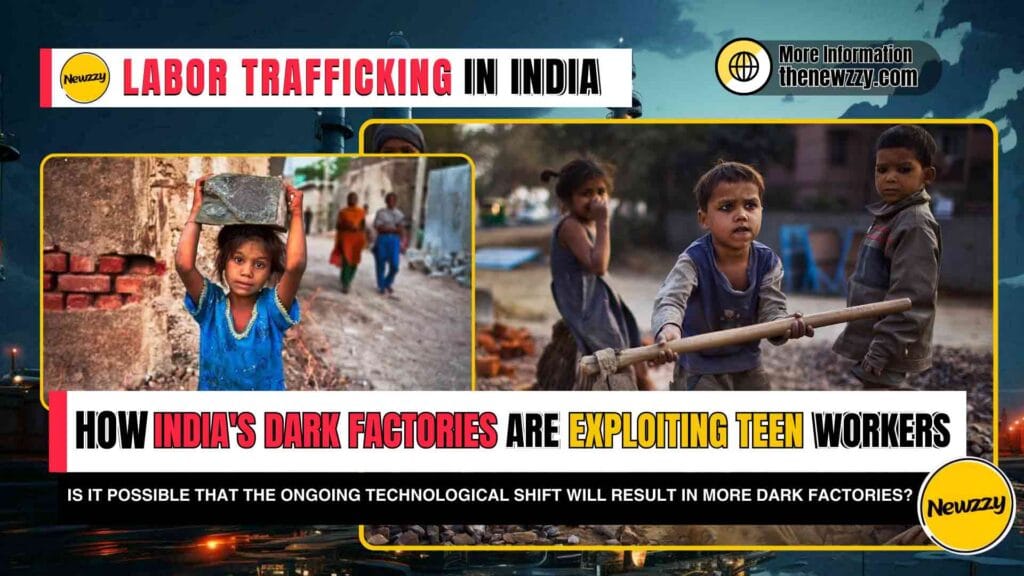

Human & Labor Trafficking in India: How much is the number of those caught in human trafficking in India? As many as 8 million people — that’s about the same as the population of New York City — are affected.

The issue of human trafficking continues to be an issue in India’s region. Among current regions, those living in South Asia and the Pacific are the most likely to be enslaved than people in other regions. It is estimated that most people living under modern-day slavery are united under the Asia Pacific umbrella, making up 62% of these cases.

The recent UN report found that the region made up by Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka had more children affected by human trafficking than any other region except for Sub-Saharan Africa.

Table of Contents

What does the Human Trafficking Problem Look like in India?

Labor trafficking in India

Over half of the victims are in restavek or bonded labor, toiling from 12 to 14 hours every day in brick kilns, at textile plants, on farms or in stone quarries. Sometimes, they got fooled into accepting work with hopes of big progress, only to realize they were charged high interest rates, leaving them with a debt they cannot get rid of.

They are often subjected to rough work and live conditions and their families are, too, while their bosses treat them as mere commodities. There are families in which the financial debts passed on from deceased workers fall on their children, siblings or parents.

Labor trafficking in India: Traffickers used cash advances to lure workers who were out of employment due to COVID-19 and held them in bondage through the debts they were meant to clear.

Low-skilled work, like domestic help and construction, attracts many Indian migrants and they often become victims of labor trafficking at places such as the U.A.E. and Malaysia.

Sex Trafficking in India

Since half of all the persons in the modern-day slavery are into forced labor, the second most common type of trafficking is sex trafficking. (Forced marriage, forced begging, forced criminality are other types of human trafficking identified in India.)

Though trafficking occurs irrespective of gender, largely women and girls are trafficked for commercial sexual exploitation. Girls are deceived by traffickers who promise them a supposedly good job; they lure the girl into a fake romantic relationship, or they buy her from a destitute family or outrightly kidnap her.

Sex Trafficking in India: Aside from really cruel circumstances where at just 12 years of age, a girl is sold into sex trafficking in rural communities, some others are forced to attend to the needs of 20 to 30 customers a day. Juvenile sex trafficking happens in small roadside shacks situated somewhere on a highway where a truck driver pulls over, pays a few bucks, and abuses a child. Sex trafficking also happens in dance bars in the city, downstairs locked rooms in some dark alley in a big city, hotels in secret levels, or even inside someone’s home.

Who is affected by human trafficking in India?

Human trafficking in India harms the most vulnerable sections of society. The most at risk are those from the lower social strata living in poverty, and without a well-knit family structure and even illiterate.”

In India, sometimes women and girls from the lower “Dalit” caste are “married” in a ceremony to the local temple deity, and they become, in effect, sex slaves for the higher caste villagers.

Often for sex trafficking, women and girls are deceived into taking fake jobs in India from Nepal and Bangladesh. The traffickers sell women and girls from Central Asia, Europe, and Africa for commercial sexual exploitation in Goa State.

Despite Legal Ban Teen Workers & Children Toil in India’s Mines

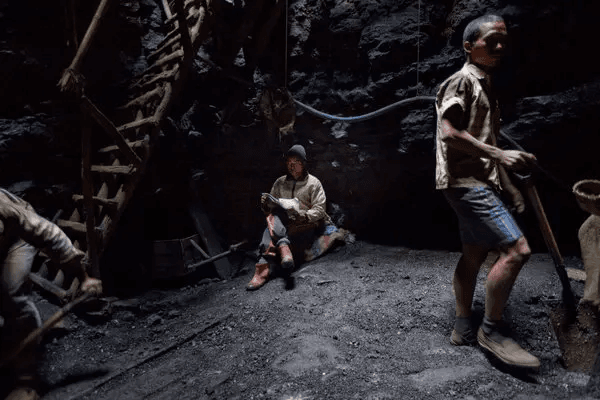

Labor Trafficking & Exploiting: The teenage miners would descend 70 feet down the wobbly bamboo staircase into a dank pit and then claw their way into a black hole about two feet high, crawling some 100 yards in the mud before their work of digging coal truly began.

They were in T-shirts, pajama-type pants, and short rubber boots: no hard hat, no steel-toe boot. They’d tie some kind of rag on their head to hold a tiny flashlight, with wax or cloth for their ears. And they’d stare at death all day long.

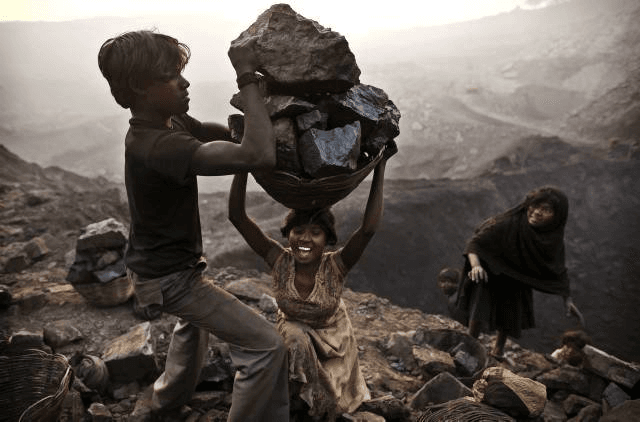

Just two months before the full force of a landmark 2010 law bids every Indian child between the ages of six and 14 to be in school, Unicef estimates some 28 million children go to work. Child labor exists everywhere: shops, kitchens, farming, manufacturing, construction. A few days ahead, India’s Parliament is likely to put forth yet another law banning child labor, but even activists say that yet more laws, however welcome they are, may not solve one of India’s most intractable problems.

“We have very good laws in this country,” says Vandhana Kandhari, child protection specialist with Unicef. “The problem is our implementation.”

And with causes including poverty, corruption, decaying schools, and absentee teachers, there is no better example of the problem than these Dickensian “rathole” mines in the state of Meghalaya.

Meghalaya is located in India’s isolated northeast, a stump of land wedged between China, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. They are tribal and Christian by nature, and they had languages, food, and facial features that looked as much Chinese as Indian.

Labor Trafficking & Exploiting: According to 17-year-old Suresh Thapa, he has worked in mines near his family’s shack “since he was a kid,” and he expects that his four younger brothers will do so too. A tarpaulin and stick shack near the mines is where Suresh and his family live. There is no running water or toilet, nor heating inside.

Some days ago, Suresh was sitting outside his home sharpening the pickaxes of both himself and his father, since he must do that twice a day. His mother, Mina Thapa, sat nearby, nursing an infant. She said that Suresh chose mining himself.

According to India’s Mines Act of 1952, no person under the age of 18 may work in a coal mine, but Ms. Thapa stated that enforcement of this law would put her family to harm. “We must have them work for themselves. No one is going to provide us with money. We have to work and feed ourselves.”

Children working in Meghalaya’s mines is not something that is hidden. Suresh’s boss Kumar Subba noted that children work in mines all throughout the Kingdom.

“Mostly the ones who come are orphans,” said Mr. Subba, who supervises five mines with about 130 employees, who together produce some 30 tons of coal per day.

He said that working conditions were dangerous inside his mines and other mines in the region. The mines he operates belong to a state lawmaker.”

Labor Trafficking Case & Investigation

Labor Trafficking case: In 2010, Impulse, a Shillong-based nongovernmental group, reported the discovery of 200 children as young as 5 years old working in 10 mines within the region. Group members believed that at least 70,000 children were laboring in mines all over the United States.

As a result of its investigation, the Indian press published photos of children working in terrible situations. State officials strongly denied that anything about child labor was happening in their country.

Investigations after the incident were led by the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights and Tata Institute of Social Sciences which is known for its high-quality investigations. It was found that the use of child labor exists in the factories.

Despite the monsoon halt on most of the mines, the Tata group found that 343 children under 15 were still working in 401 mines and seven coal depots. Though the group wanted to investigate further, the threats from local groups to injure them made the researchers stop collecting data.

Though salaries are high, the report from Tata points out that it is still hard for mine managers to recruit enough people locally. Most local people do not want these jobs, so children and other workers are brought from Nepal or Bangladesh, with advocates claiming that this is a form of trafficking. It is common for people to soon fall into the well-known scam.

The pay is good, but because they deliver food, water and basic supplies to the camps, the price is always very high. As a consequence, most of these children are not able to participate in sending money back home or earning an income to depart.

Is it Possible that the Ongoing Technological Shift will Result in Dark Factories in India?

India’s Dark factories: With the growth of disruptive technologies, fully automated factories may soon become a norm. With the advancement of the “factory of the future,” using autonomous production in lights-out factories will likely increase across various manufacturing companies.

With mature and advanced automated machines and reliable MOM software, running factories without employees is now a realistic possibility. The software makes it possible to see what is being produced automatically, as it does not rely on additional help. Also, people can monitor and manage operations remotely and get warnings to perform additional duties or take action if required.

It is possible that some factories can work well with a small amount of lighting, using only certain dark areas where true efficiency is needed. Thus, companies can use autonomous technologies for manufacturing without having to completely shut down human staff.

What are the benefits of using India’s Dark factories for Production? Now, Dark Factory is becoming a reality and soon it could be the standard for mass manufacturing. Several causes are behind the growth of lights-out production, including:

The main advantage of dark manufacturing is that it is cost-effective. Not having workers means no entry-level salaries and robots can manage tasks in conditions that are dark and never reach an ideal temperature, resulting in lower utility costs.

| 1. It Cuts Down on Environmental Issues – Lights-out manufacturing is an eco-friendly approach that brings down issues linked to the environment. Newer industrial robots use less power. Additionally, robots are highly accurate which lowers the amount of waste and scrap in manufacturing, as they do not release any carbon emissions. |

| 2. Improved efficiency and improved product quality. With one robot able to do the work of many employees, plants can boost their work output significantly. Furthermore, when products are made with accuracy and precision, the quality is improved. Since robots are programmed to follow the exact instructions, all parts are created close to the same size and shape. |

| 3. Eliminates Labour Shortages: Many manufacturers have struggled to find enough workers, especially those with special skills. A smaller group of people are now interested in manual labour, making it challenging to find workers. Thanks to robotics, workers can now stay in light areas and use machines to place the robots in working positions, solving this safety issue. |

Labor Abuses in India’s Dark Factories

Thanks to global supply chains, brands can find materials and make their products in different countries to keep expenses low. On the other hand, the existence of multiple subcontractors creates a disconnection between producers and the companies they are associated with.

Without full awareness of all steps in the supply chain, companies overlook any injustices happening in factories. Some companies are able to dodge certain rules by taking advantage of the hidden nature of their deals. Individuals working in clandestine sites aren’t able to ask for fairness or safe working conditions.

Labor Abuses in India’s Dark Factories: People who run dark factories are not easily supervised because their identities cannot be revealed. Due to their dependability on their jobs, laborers cannot refuse work that puts them in harm’s way. Because of this, workers are easily taken advantage of by their employers.

Secrecy Often Creates Problems That Go Unseen by the Public

Since dark factories are not openly seen, any abuses that happen there usually go unnoticed. Work is given to others, who then give it to others, to hide the identities of the end producers. It is common for locations to change often.

People in these jobs are often wary of sharing information in case operators notice or get mad. Nobody outside the factories can see the real conditions in which products are made. Buying products made under harsh conditions means consumers unknowingly help those abusive systems grow. A lack of transparency in global supply chains makes it possible for human rights to be abused and keeps bad practices hidden.

Government Oversight & Accountability on India’s Dark Factories

India’s Dark Factories: As people learn about the dark factory issue, activists try to ensure companies are held more accountable for what happens in their supply chains. They urge firms to place ethical sourcing higher than saving money alone. Main brands should monitor and control their subcontractors, ensuring production in every primary workshop.

It is the government’s job to defend its citizens, whether they are employed abroad or in undisclosed parts of the country. Better rules and monitoring can reduce the likelihood of serious human trafficking that goes unnoticed. These protections would allow people to inform others about dangers at work in a secure way.

Although being aware of every step in the supply chain is difficult, companies should actively search for risks. If companies, policymakers and advocacy groups come together, it is possible to address and end environments that force modern slavery.

It is a basic right for society to tackle the issue of harm to vulnerable workers. dark factories express the human cost that is often hidden in production networks today. Schemes kept out of the public eye help these abuses continue, leaving workers with few options for help.

MNCs Circumvent law on Technicality

It has been reported that many white-collar workers in the Indian private sector clock over 12 or 14 hours of work every day.

The Factories Act of 1948 ensures that anyone working more than 8-9 hours a day or 48 hours in a week should be compensated an extra wage for hours worked. The act only allows for these benefits for factories or employers with employees referred to as “workers.”

In the eyes of the law, since Rohan and Aditi are not classified as factory workers, extra compensation for overtime will not be granted.

According to Mahesh Godbole, who was working in HR about 40 years back, companies can get around overtime rules by calling their employees officers or executives, since these categories are not included in overtime laws meant for ‘workers.’

Despite contacting Meta, Apple, Amazon, Google, Ola Consumer and KPMG by email, none of the companies answered our questions about overtime practices in India.

Laws that are not adapted for current times

Due to remote working, it is more challenging for employees of MNCs in India to separate their job and personal lives. She feels that the work-life balance idea is only a tool used by companies, as she has spent countless hours at her job with an Indian multinational over the last five years.

Now that the pandemic is over, people who work from home are expected by their managers to be reachable all the time. Another example is that the protections given to Indian workers by the laws issued in 1947 cannot cover the changes seen in the current labor force.

Can the laws be challenged?

Regarding MNC workers seeking overtime, Suresh Chandra Srivastava expresses that no laws or practices give precedence for such cases. He states that last year, the Supreme Court of India held that government workers are not eligible to receive double overtime pay under the Factories Act.

The court emphasized that the law targets factory workers, not government staff, whose management is under different systems of rules and regulations. Therefore, government employees were not given the option to be paid double for overtime.

The apex court’s decision demonstrates how existing labor laws are not sufficient. The same legal challenges will affect both MNC employees and government employees as a result of their similar status. However, in 2022, the Achalpally Industrial Relations Court in Chennai decided in a labor court case that was brought against a business owner.

The court overruled the Indian software MNC, stating that an IT analyst could be considered a “workman” just as any other employee.

Sophy pointed out that according to this system, where the nature of the job counts and not just the pay, most software engineers have a chance to dispute their working conditions by claiming under the Industrial Disputes Act.

From Economic Liberalization to Now

India’s Dark factories: Many experts examine the period following India’s move to economic liberalization in 1991 which led to a fast-growing private sector and increased demand for employment. At the same time, though, weak government regulation meant private companies were able to take advantage of loopholes in old laws, they point out.

It was pointed out by Sophy KJ that, over the years, trade unions stopped labor from being exploited. Yet, after liberalization, contractualization and outsourcing became the common way the industry was run.

Being a contract worker meant that employees couldn’t unionize without immediately being at risk of losing their income. Because of this change, trade union membership has decreased significantly since the 1990s.

There have been cases where small, individual unions appear in the private sector, but without help from bigger unions, employers have bought them out. As a result, white-collar workers today suffer from reduced rights and protection, as union involvement is extremely low in their field.

What does the industry say?

India’s Dark factories: Prasheel Pardhe has been working in the HR field for over 25 years. According to Pardhe, working in the IT sector, overtime payment is not available in India because the salaries are already considered competitive for the industry.

In order to have good IT professionals on their team, companies in India must guarantee they are paid competitively, he shared. Besides, employees receive both compensatory leaves and performance bonuses as part of their rewards.

References

| 1. Human Rights Watch/Asia, Rape for Profit: Trafficking of Nepali Girls and Women to India’s Brothels (New York: Human Rights Watch, June 1995). | 2. All dollar amounts in this report are in U.S. dollars. |

| 3. Pradeep Mehta, “Cashing in on Child Labor,” Multinational Monitor, April 1994. | 4. Ministry of Labour, Annual Report 1994-95, p. 95. |

| 5. Commission on Labour Standards and International Trade, Child Labour in India: A Perspective, June 10, 1995, p. 32. | 6. Tanika Sarkar, “Bondage in the Colonial Context,” Patnaik and Manjari Dingwaney, eds., Chains of Servitude: Bondage and Slavery in India (New Delhi: Sangam Books, 1985), p. 97. |

| 7. Mahajan and Gathia, Child Labour…, September, 1992, p. 24. | 8. Y. R. Haragopal Reddy, Bonded Labour System in India (New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications, 1995), p. 82. |

Similar incidents took place across India in the mid-1980s. See, e.g., Ajoy Kumar, “From Slavery to Freedom: The Tale of Chattisgarh Bonded Labourers,” Indian Social Institute, 1986, p. 8, reporting that bonded agricultural laborers who attended meetings with labor activists were publicly beaten and driven from their homes.

For more updates follow: Latest News on NEWZZY