India is currently working to address an existential question of the public mental health sector, and it can be summed up by the fact that millions of citizens survive with mental health problems without seeking help. Such a phenomenon, which can rightly be called a silent crisis, is a major social problem that does not only concern the personal distress but is a serious matter that therefore affects national well-being and economic security.

World Health Organization (WHO) has given a elaborate definition of health by stating that health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well being rather than absence of disease. This point of view supports the idea that mental health can be discussed not only as the absence of the disease but also as a part of the whole health, which is closely integrated with physical health and behavior. This kind of a large-scale look is important in understanding the far-reaching consequences of mental health conditions.

Read About: Brain Fog | Why Young Minds Are Slowing Down in a Fast World? The New Health Crisis 2025

Table of Contents

Mental Health Issues in India

The extent of the mental health issues in India is massive. According to the estimation of WHO, there is a burden of 2443 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) by 100,000 population that represents the significant healthy living years lost to mental illness. Making this worse, the age-adjusted rate of suicide is alarming at 21.1 per 100,000 population population apparently due to the extreme forms of psychological distress that is untreated and widespread in the country.

More than human losses, there are the economic consequences which are truly overwhelming. It is estimated that mental health conditions will cause an economic damage of USD 1.03 trillion to India between 2012 and 2030 largely because of lost productivity.

This colossal number does not only make mental well-being a proclaimed object of social welfare but also stipulates this issue as such one that plays a crucial role in definition of national economic growth. This permeant quality of what has been termed a silent crisis, however, means that despite the sheer magnitude of the crisis it is often on the fringe of political attention and on the edges of the limelight within society, resulting in millions of people not getting the support they deserve.

The Startling Truth The Info on the Studies

Mental Disorders-Prevalence and Burden

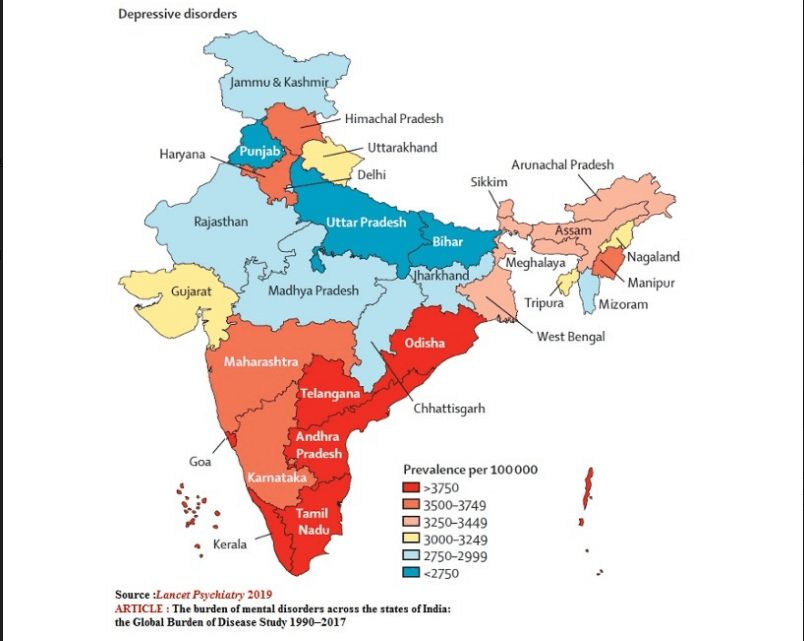

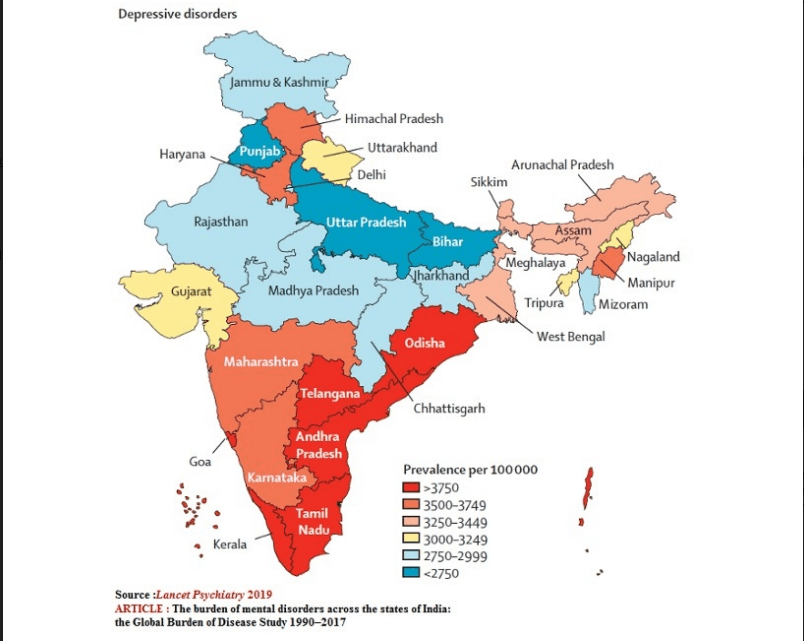

The objective realities of mental health situation in India demonstrates a disaster of gargantuan scale. The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS 2015-16) indicates that the problem of mental ill health is huge with about 14 per cent of the Indian population needing mental health intervention. This equates to an enormous figure with a desperate need of treatment. Further Statistics by the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences(NIMHANS) in 2017 counted about 197.3 million citizens in India to be affected by mental disorder which means how widespread the problem is.

This is supported by government statistics, which reports that approximately 150 million people in India were in need of active treatment of mental disorders, and this is a huge immediate need.

The sheer distress can be described by specific rates of prevalence of common disorders. Estimates of childhood nonfatal depression per 100,000 children were higher in U.S. India had an estimated 38.4 million cases of total cases of anxiety disorders or 3.0 percent of the population and 56.7 million estimated cases of total depression disorder or 4.5 percent of the population in 2015.

There is a specially alarming problem regarding the mental health of young people in India. The national report on the student suicide rates shows one of the highest suicide rates in the country compared to other countries in the world and just as the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) states one student commits suicide per hour.

The levels of depression or anxiety are reported by over 50% of the younger Indians, which points to a major crisis in a demographic extremely important to the country. Although the prevalence of adolescents in urban (4.1%) indicated by the NMHS 2015-16 was higher as compared to rural communities (1.5%) this may be because there are more urban stressors or perhaps a more competent assessment in urban locations. This prevalence was almost 20.6 percent among the aged where the reverse was true with the elderly in the urban areas registering greater depression rates (22 percent compared to 17 percent of those in rural areas).

The Stark Treatment Gap: Millions of the untreated

Even though the targeted population is immense, the gap between the need that has been voiced and the actual care is immense. The percentage (70 % to 92) of individuals with mental disorders in India actually receive treatment is appalling.

The situation exposes a very important phenomenon, which is the underestimation paradox. The fact that the study of IIT Jodhpur found that the prevalence of self-reporting mental illness is below 1% is startling compared to the much higher prevalence rates of NMHS/NIMHANS indicating that 14 percent or 197.3 million individuals need to be intervened. This is not only a matter of a treatment gap, but an essential identification gap.

That according to the 75th National Sample Survey, which was applied in IIT Jodhpur, there was total reliance on the self-report leads to a strong suggestion that even official prevalence rates, though startling, would only be the tip of what is actually present since other studies point that the actual burden would be considerably higher.

Why Indian Youths are having more Mental Health Issues?

India is prone to bad mental and emotional health issues of the youth and adolescents population, which is a vulnerability to this demographic dividend. This can be assessed by the alarming fact that India has one of the highest rates of student suicides in the world with one student committing suicide every hour . Economic Survey 2024-25 clearly correlates the prosperity of India in the future to the mental health of the young population by saying that the demographic dividend is being ridden on skills, education, physical health, and most importantly the mental health of the young population.

This sets a definite cause-and-effect relationship: the current untreated mental health crisis in youth directly takes the economic potential and social stability of India, turning a problem in a certain area of public health (physical health) into a national crisis of growth. This is further compounded by the post-COVID digital addiction surge which shows that this does not represent old or unchanging challenges but require specific interventions.

Mental Health Statistics India

| Metric | Data Point |

| Population Needing Intervention | 14% of population (NMHS 2015-16); ~197.3 million individuals (NIMHANS 2017); ~150 million needing active treatment |

| Depressive Disorders (2015) | 56.7 million cases (4.5% of population) |

| Anxiety Disorders (2015) | 38.4 million cases (3.0% of population) |

| Treatment Gap | 70% to 92% of affected individuals |

| Self-Reporting Rate (IIT Jodhpur study) | Less than 1% |

| Age-Adjusted Suicide Rate | 21.1 per 100,000 population |

| Projected Economic Loss (2012-2030) | USD 1.03 trillion |

The Causes of Underreporting and Failure to Seek Help

Underreporting of mental conditions in India is not random behavior; it is the result of numerous social, financial and structural factors deeply embedded in the society. The knowledge of such barriers is key to intervention development.

Societal Stigma and Cultural Beliefs which are Pervasive

The most crucial and wide-reaching hindrance towards accepting mental health issues in India and addressing such challenges through professional support is stigma. The intense fear of being considered as someone who is mentally ill, in many instances, informs individuals to put off or all together, fail to seek the appropriate support. The mental health as a subject is often perceived with shame and dishonor in most cultures prevalent in India.

Conventional thinkers can hold the view that mental illnesses are caused by weakness of morals, character deficiencies, bad karma, sins committed in a former existence or even by ghosts or supernatural powers. Active suppression of free discussions and the reinforcement of the falsehood that seeking help is one of the peculiarities of personal failure or weakness are enhancements of this cultural narrative.

Indian society attaches the utmost importance to the notion of family honor also known as izzat and in many cases mental illness is viewed to bring stigma on the whole family. This belief causes a lot of pressure to hide resulting in people opting to remain quiet rather than to seek support as a result of the fear of being judged by the society. As a result of fear, ridicule and social distancing, the stigma in the public also propagates another form of fear, social ridicule and social distancing, especially in rural and semi-urban locations.

Social and Economic Ineasting and Economic Categories

The willingness of reportment of mental health issues significantly depends on the economic status. In another study conducted by IIT Jodhpur, the socioeconomic gap was very profound and self-reported mental disorders were recorded to be 1.73 times higher among the richest income segment than among the poorest in India. The fact can be highlighted to be more impoverished individuals and those with better financial means differ significantly in terms of helping themselves with mental issues through recognition and seeking assistance.

Apathy in Mental Health Literacy and Awareness

General ignorance and an exclusion of mental health literacy (MHL) are the most basic cause of stigma, and a defining obstacle to early identification and effective treatment of mental illness. People are not aware of the symptoms, causes, and treatability of mental disorders as most of them are simply not familiar with the conditions.

There is a misconception that mental illness is the same as an intellectual disability or is related to the risk to others and instability. The latter continues with fear, avoidance and negative labelling in communities. The problem of mental health being not seen as health problem in general, and as legitimate illness problem in particular, contributes to active gaining of help in both urban and rural communities.

The fact that informal sources of knowledge about mental health issues are prevalent is a worrying trend among many citizens, including frontline health workers such as Accredited Social Health Activists to which (73.1%), they turn to and the lack of more formal methods such as training or education.

Demographic Inequalities Gender, Age, Rural-urban Divide

The burden of mental illness and the impediments to help-seeking are not evenly spread in the population and more specific disparities have been reported across population groups.

- Gender: Women are also overrepresented in mental health conditions in that they are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to have Common Mental Disorders (CMDs) than men. They often face a so-called double stigma as they are first stigmatized due to having a mental illness and second stigmatized due to the disregard of the presumed gender norms of obedience, emotional control, or care provision.

Health problems associated to the mind in women are either ignored or written off as being hysterical, moody, or just something that occurs because of lack of marital satisfaction. Another layer of vulnerability of rural women is gender disadvantage in combination with poverty, poor physical health, high-level caregiving burdens, and exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV), which all substantially increase the risk of CMDs.

- Age: Depression among the older population attracts great concern, where nearly one in every five old individual reports having depression, yet the research demonstrates no conclusive urban-rural or malegender gradient among elderly people. Conversely, the rate of depression and anxiety is very high and on the rise among youth and adolescents, a factor that has been worsened by surge in digital addiction since the onset of the COVID epidemic.

- Rural-Urban: Mental health concerns are usually more reported in the urban setting (e.g., 13.5% in urban communities versus 6.9% in rural settings on all mental health problems ; 4.1% on the adolescents in the urban setting versus 1.5% on the rural adolescents ). Nevertheless, rural communities face some special and acute access impediments, such as a lack of mental healthcare provision conducive to women, the significant scarcity of qualified mental health specialists with an awareness of rural culture, and underlying widespread communal stigma that tends to be more intense in the rural setting, especially compared to big cities.

In direct relation to socioeconomic status and reporting behavior, the IIT Jodhpur research shows that those among the higher-income bracket are more likely to report on mental health issues by a factor of 1.73. This implies that wealth may also serve as a cushion to the all-embracive effect of stigma, which helps in capturing care.

The Indian family system brings about a contradictory pattern. On the one hand, a family is usually a primary source of mental health care, and such a structure becomes the source of emotional support. Research studies have gone to point out superior compliance with the treatment and reduced hospitalization visits by schizophrenic patients staying in joint families.

Conversely, the ultimate notion of family honor (izzat) and classical hierarchical relations, especially affecting daughters-in-law may turn out to be formidable impediments. Elders have been found to be the gatekeepers and have the power to regulate either access to care and/or financial resources and emotional abuse may be not even recognized because of the tradition of emphasizing family honor instead of individual well-being.

Systemic Repercussions: The Wide-Ranging Implications

Unaddressed mental health crisis in India has a deep and extensive systemic payoff that cuts across sectors including the economy, social and health sectors.

Economical Cost: Avoidable Productivity and National Expense

A shocking economic cost is the most measurable impact of this. The risk of losing USD 1.03 trillion in potential prosperity by 2030 because of mental health conditions is one of the major losses of national resources. Such a huge cost burden can directly be noted to be the result of poor workplace performance, high cases of absenteeism, and low efficiency in several industries.

A basic failure of mental health funding of the so-called trickle-down theory can be seen in its disproportionately small allocation of funds and its gross underutilization of funding: in that mental health consistently gets less than 1 percent of the overall health budget despite significant underutilization of those funds. Although the economic cost of mental illness on the country is enormous, there is hardly any significant investment in terms of finance and even this minimal financing has no full utilization on the ground.

Mental Health Professional and Infrastructure Critical Shortages

The absence of mental health professionals in India is alarming and widespread and is a major cause of the huge treatment gap. The psychiatrists ratio is comprised of 0.75 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, which is a severe contrast to the WHO suggestion of over 3 per 100,000. The ratio is even worse in the rural environments where access is the most limited. The shortage is more complete among other important cadres of mental health: clinical psychologist has a 97 percent deficit and psychiatric social workers have a 90 percent deficit.

This deficit reaches to the loss of breadth: there exists a hugely dearth of training facilities, that cannot satisfy the supply of new professionals. In addition, psychiatry only receives a small amount of time in undergraduate medicine (1.4 percent of lecture time of 3.8-4.1 percent on internship) and the training of general practitioners is quite inadequate to help them to competently handle frequent mental health issues.

Poor Budgetary allocation and use of funds

According to the great burden, the allocated Mental health spending is below 1 percent of the overall health budget in India. This was only 0.8 of the total health budget in 2023 which is US 88 million. This slight budget of 75 million dollars has been highly focused on two tertiary academic institutes of mental health (NIMHANS and Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health), lending serious concerns about health equity. Such concentration of resources at the tertiary level lacks the incorporation of the majority population that needs primary or secondary services.

National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) theoretically tasked to provide 90 percent of the mental health services to the population is allocated a minimalistic amount of five million dollars, and often this is not used as it is lost in poor planning and priority setting. To use the example, during 2020-21, only 2.64 million of the 5 granted funds to NMHP were spent.

What is more spectacular, in 2018-19 and 2019-20, 96 and 93 percent NMHP funds were not used, i.e., were returned to the national government. Likewise, in the case of District Mental Health Program (DMHP), not all the amount of funds provided was used by states in 2015-2021 (only 38.11%, or 6.5 billion dollars were used). This demonstrates a critical system weakness of the absorptive capacity and implementation bottlenecks where even when the funds are availed, they are not successfully reached by the recipients owing to the inability of exceptional planning and execution between the state and the central government.

Pathways to Change: Strategies of a Mentally Healthier India

The problem of mental health that overwhelms India needs a holistic, long-term, cross-sectoral approach. It needs to undertake a strategic change to shift towards a reactive, narrow to proactive, holistic and inclusive mental care system.

Policies and legislative mechanisms

The field of mental health has witnessed remarkable achievements achieved in India with regard to giving the framework of base policy and laws. A participatory and rights based approach to provision of good services is supported by the National Mental health Policy in 2014. This policy was set to treat mental health conditions in a multi-faceted way as well as incorporating mental health treatment into primary health care, enhancing human workforce, and a better access to treatment.

In spite of these progressive policy and legislative frameworks, there is a great difference that exists between policy intent and actual on-the-ground implementation. Even though the Mental healthcare Act 2017 and National Mental Health Policy 2014 document elaborate plans, current tendencies of persistent under-utilization of funds allocated to various programs such as National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) and the District Mental Health Program (DMHP) suggest the extensive policy-practice gap.

Enhancing Human Resource and infrastructure.

The most important step is to deal with the severe lack of mental health professionals. One of the strategies will be to train general physicians so that they can respond to mild-to-moderate mental health cases, thus making mental healthcare part of the primary healthcare services. NIMHANS is conducting a Diploma in Community Mental Health of Doctors based on the online program, which targets improving the theoretical and practical skills in primary care of mental disorders.

Innovation Utilization of Technology and Digitization

Digital solutions provide an effective means of breaking the distance between people and improving the access to mental healthcare, especially in a large and many-faceted country as India is. Tele MANAS, a national tele-mental helpline, has been supporting in real-time tele-counseling, referrals to psychiatrists, and mental health awareness campaigns through digital means to ensure that it is accessible in rural and remote locations.

Online counseling websites like Click2Pro and BetterLYF provide easy and cheap online access to a virtual one-on-one therapy sessions (video, call, chat), psychiatric consultation, free-assessment, and self help program with emphasis on confidentiality. Wysa is an anonymous, stigma-free, evidence-based 24/7 wellbeing coach delivered through artificial intelligence. It is used by individuals, organizations and healthcare providers.

Conclusion

The paradox of a huge burden of illness, cloaked in a general culture of silence, is characteristic of the mental health situation in India. The statistics clearly indicate that around 150 to 200 million people need mental health care but unfortunately 70-92 percent of the large population is still not getting any medical care. This is not just personal suffering but a structural failure, and it is supported by a visceral stigma as well as serious economic hurdles, an extreme insufficiency in mental health literacy, and tremendous shortages in both workforce and infrastructure.

The fact that this crisis will cost the global economy up to USD 1.03 trillion by 2030 only demonstrates its extensive consequences affecting the national progress and efficiency.

References

- https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1919922

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

- https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2034931

- https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_2

- National Mental Health Survey, 2015-16 – Summary Report_0.pdf

- https://pib.gov.in/PressNoteDetails.aspx?NoteId=153277&ModuleId=3®=3&lang=1

- https://sansad.in/getFile/rsnew/Committee_site/Committee_File/ReportFile/14/187/148_2023_9_17.pdf?source=rajyasabha

- https://www.who.int/india/health-topics/mental-health

- https://mohfw.gov.in/?q=pressrelease-40

- Grover S, Shah R, Kulhara P. Validation of Hindi Translation of SRPB Facets of WHOQOL-SRPB Scale. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:358–63. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.122225.

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Algorani EB, Gupta V. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Coping mechanisms.

[PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, et al. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:939–91. doi: 10.1037/bul0000110.

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - https://old.iitj.ac.in/press/press_view_file.php?path=..%2Fpress%2Fuploads%2F30-January-2024%3B+%28ENGLISH%29+Press+Release+-+IIT+Jodhpur+study+finds+low+self-reporting+for+mental+disorders+in+India+%289%29.docx+-+Google+Docs.pdf

- Banandur, Pradeep & Gopalkrishna, Gururaj & Varghese, Mathew & Benegal, Vivek & Rao, Girish & M Sukumar, Gautham & Amudhan, Senthil & Arvind, Banavaram & Girimaji, Satish & Kommu, John Vijay Sagar & Bhaskarapillai, Binukumar & Thirthalli, Jagadisha & Loganathan, Santosh & Kumar, Naveen & Sudhir, Paulomi & Satyanarayana, Veena & Pathak, Kangkan & Singh, Lokesh & Mehta, Ritambhara & Modi, Bhavesh. (2021). National Mental Health Survey of India, 2016 – Rationale, design and methods.

- Chandra, Prabha S. & Ross, Diana & Agarwal, Preeti. (2020). Mental Health of Rural Women. 10.1007/978-981-10-2345-3_12.