Missing Women & Girls, India is a country of more than 1.4 billion with a development process on the brink of some transition. Although considerable improvement has been recorded in the scores of socio-economic indicators, there is a grim shadow disrupting its growth, the insidious, and pervasive problem of millions of its women and girls missing in official data.

Read About: Indian Students US Visa Report July 2025: US Faces 70-80% Drop !

Table of Contents

Why there are Millions of Missing Women & Girls in Official Data?

This negligence is not just a plain statistical aberration, but a naked witness to the inherent and entrenched gender discriminations and structural disparities that infuse the Indian society. Deviating between sex-selective practices to come to demographic imbalance and not recognizing the economic efforts of unpaid labour, or facing gross deficits in formal workforce per statistics, and persistence of structural discrimination, the mainstream discourse continuously misses out in documenting the actual lives and economic trends of half of the population.

The article expounds on the multidimensional aspects of how the data architecture of India makes women and girls vanish, the demographic, economic, and social implications of such an omission, and the need to step out of the current paradigm of data gathering and policy-making to actually capture the missing millions.

Millions of Missing Women & Girls in India’s Official Data

The most severe evidence of the invisibility of women in the official discourse of India is the horrific shortage of population. India had a shocking number of 63 million missing women as pointed out in the 2017 18 Economic Survey. This number is the amount of women who are not alive in spite of the fact that they statistically should be.

The outcome of severe gender discrimination is an inevitable result of the problem. Augmenting this number, the survey also concluded that an additional 21 million girls were viewed as unwanted and this is a frightening confirmation of the social preferences representative in terms of being subjected to sex-selective abortions, postnatal neglect, and death rates overwhelmingly high in relation to that experienced by their male counterparts.

Why there’s a Population Imbalance in India?

This population imbalance in india can be traced back to a multifaceted combination of cultural, social and economic forces. High levels of son preference generally assisted by patriarchal customs that favor sons in terms of providing usable and non-usable assets in old age and propagation of family name tend to result in such dramatic and drastic solutions to prevent or eradicate female childbirth. Prenatal sex determination technologies because they are readily available and illegal have enabled sex selective abortions, especially in areas where there is the greatest demand of sons. After birth, females are regularly discriminated against in nutrition, health and education access, which conversely brings around greater mortality during the elementary age.

Gender Bias in Indian States

The tilted sex ratio of birth, especially in the economically well off states such as Haryana and Punjab is a decisive pointer to this underlying gender bias. Economic development has not automatically led into gender equality since such progressive states still report some of the lowest rates of sex ratios at birth. Agricultural processes, land titles and Dowry issues can be cited as some of the reasons why daughters are avoided in these regions, creating a cliched-like system which must be broken in favor of daughters.

The net effect in the long run of these demographic dislocations is devastating and will result in excess men, social instability, possible gender based violence, and an otherwise lopsided society that cannot develop fairly. The inability to implement a correct count and account of these missing millions does not only conceal the actual level of gender discrimination but also hinders development of targeted interventions that are required to implant this very grave human rights concern.

Unpaid Female Labour Force in India

In addition to the demographic shortfall, there is the problem of a large segment of the contribution of women that is not counted in the totals of the economy of India which is that of the large amount of labor they perform free of charge. National surveys and macroeconomic models that tend to statistically underestimate, or in the case of women, completely dismiss the huge amount of work that women are doing in households and communities are designed in such a way that they tend to capture only those activities that are formal economy in nature.

This disparity became clearly illustrated by the Time Use Survey (TUS) 2019, a step that is very critical in terms of gauging how time is divided among the different activities. The survey revealed that the average Indian woman spends 5 hours daily doing unpaid domestic and care work, just in contrast to the men, who spend only 98 minutes doing such work. This huge gap raises an important gendered division of labour as women are disproportionately burdened with care work.

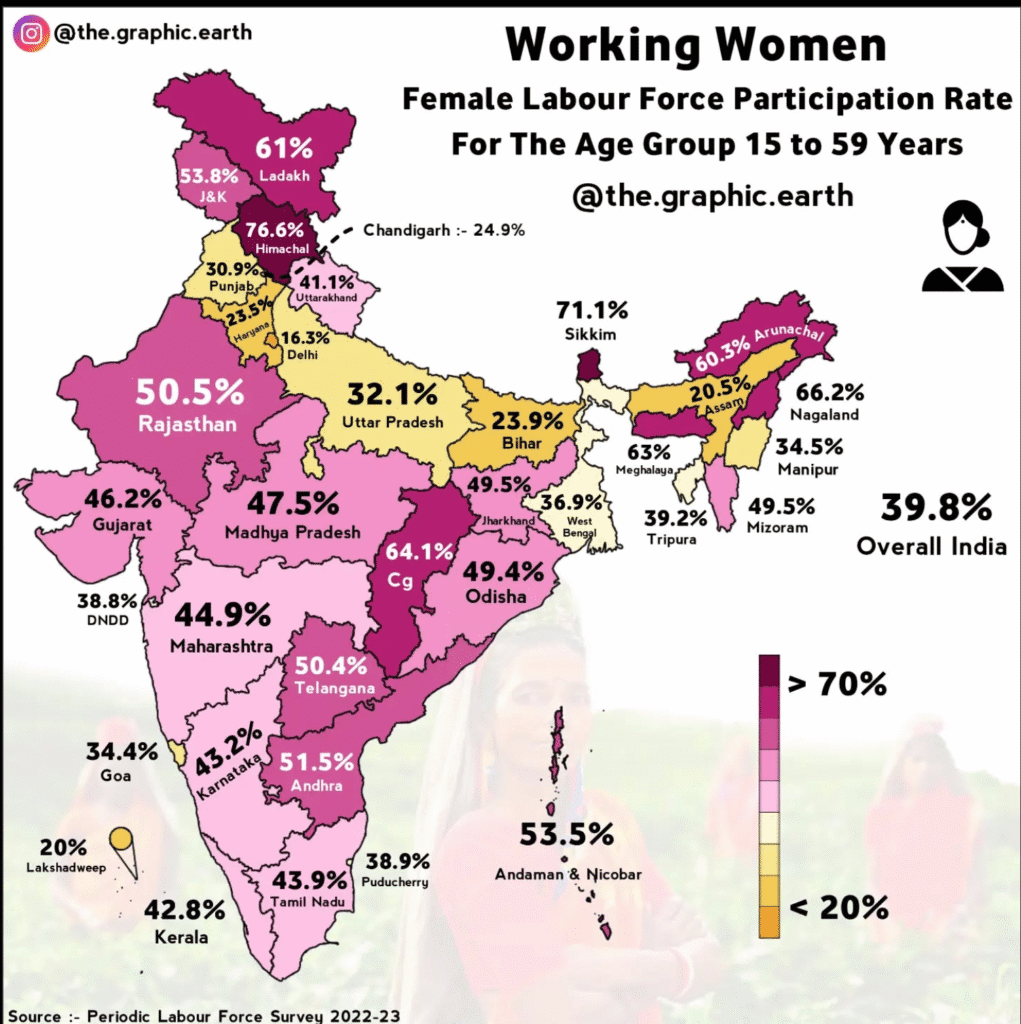

Undercount of Female Labour Force

The effects of this undercount cannot be underemphasised especially to Female Labour force Participation Rate (FLFPR). Authoritative numbers tend to record India FLFPR at a moderately low level, at around 20 percent, in historical times, although it has in the recent times experienced an upward trend. Nevertheless, given that the economic contributions of the unpaid house work that women carried out could be considered and included in the FLFPR, the estimation of the FLFPR could be adjusted considerably, and it might even reach impressive 81.6%.

It is not an academic exercise to recognize and appreciate this invisible work; to mistreat it has some serious policy implications. Failure to value unpaid care work results in an undercount of the economic contribution that women make to the national economy, reinforces stereotypes in terms of the role of women in the economy, and helps answer why social infrastructure (such as childcare facilities or other common utilities) is not built to share the burden of unpaid care work by women.

Unpaid Female Labour Force Worth is Over 22.7 Lakh Crore

Indeed, a McKinsey Global Institute report has estimated that this care work that women perform unpaid is worth 22.7 lakh crore (which is a percentage of about 7.5 in India) every year. Such a significant addition not only would paint more accurate image of what a country is producing economically, but it would also demonstrate how much it is necessary to implement a redistribution of care activities, investments in care infrastructure, and, eventually, allow women to enter the formal economy in larger numbers.

Lapses in the Statistics of Workforce and Formal Employment

The problems of measuring the economic activity of women are broader than those of unpaid labour into serious shortcomings in data on the official workforce and formal employment. The large and highly informal labour market in India, along with the growing gig sector, poses particular data collection problems that affect particularly the situation of women workers. Statistical records of the government agencies can give little idea about the nature of women participation especially in relation to contract labor, informal laborers and the micro divisions of wages, terms of work and amenities in terms of gender.

Failed Official Statistical Report About Female Economy

As an example, dashboard statistics of the National Statistical Office (NSO) and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), though offering some statistics, fail to be specific to know the state of the economy in the life of women.

Although MGNREGA dashboards could report person-days created to women, information that is often silent on dashboard indicates the daily average wages earned by women relative to men, the kind of work women are mostly expected to do, the presence of amenities such as childcare facilities at sites, among other details. Such absence of disaggregated data complicates the process of identifying particular weaknesses, tracking the process of gender equality achievement in employment and developing specific measures.

Bias Process in Women Employment

An important aspect which is nearly not recorded in government data is the discrimination at the demand side that is, the treatment of women by employers during the hiring, promotions and terminations. Although anecdotal evidence and qualitative analyses flood the scene in terms of the types of bias that women experience in job market, formal data collecting procedures do not document any of these subtle but ubiquitous facets of discrimination.

The implication of this omission is that gender equality policy interventions in the employment area tend to focus on address the issues on the supply-side (e.g., education, skills), only to neglect the problems that perpetuate inequality on the demand side (i.e., there is no action against the inherent/structural discrimination of women in the employment market).

Norms, Safety, and Access for Women in India

Admittedly, there is more than just statistical absence of women in prosperity and growth in India: The economic empowerment of women in India is significantly crippled by a network of structural compromises that surpass simple cultural mores, security issues, and lack of adequate resources and facilities. The two sets of obstacles tend to work together, deterring women to enter or stay in the wage workforce, whether qualified or not and whether they want or not.

The traditional gender role is prescribed by the patriarchal norms that tend to tie women down to the family space, and to avoid taking paid labor, especially not outside the home. Family and community pressure may be enormous and it insists on the notion that a woman is the first and foremost wife and housekeeper.

Structural Barriers for Women in India

Practical hindrances have also been added to this kind of cultural conditioning. The lack of quality education and training facilities hinders women to become employable in higher income earning fields. Unsafe transport modes, fear of personal security and harassment add limitations to the travel and movement of women to their work places in unusual hours or places and workplaces. The crippling lack of good and affordable childcare only on the part of women puts their shoulder in the superhuman task of juggling work and career, leaving them no choice but to keep one side of the coin at the expense of the other, mostly giving up work or taking up lower paying jobs.

Women’s Employment Rate in India

Although the female Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) has recently increased, reaching the mark of 41.7 percent in 2023-24 compared to around 23 percent in 20172018, it is still not as high as the world averages. This rise is positive, but it should be put in perspective. Much of this increase could be explained by women actually taking their place in the informal sector or subsistence agriculture as a necessity because of the economic situation, instead of seeing a widespread rise in well-paid and formal jobs.

The wide gap between the two shows that even though there is some improvement happening, there are still structural barriers that are hindering women economic participation to its fullness and even on an equal platform.

Loss of Productivity and GDP Rate | Economical Cost

The hiddenness of women and girls in the formal statistics and limited role in the formal economy has a heavy economic cost to India, as an enormous loss of potential and a dragger of growth in GDP. It is not just a societal problem but a very important economic necessity. It is a fact that utilizing the talent and the potential of women, the skills, and the labour resource of women is a direct result in foregone output in the economic standing.

This staggering economic opportunity cost has been highlighted in a groundbreaking study done by the McKinsey Global Institute. The report has calculated that the country stands to gain another 770 billion dollars in GDP through 2025 just because of closing the gender employment gap. This immense number demonstrates the magnitude of the changes that would be effected once gender parity is attained in the workplace.

Importance of Women in a Country’s Economy

The economy at large is a loser when women are not equally provided with educational opportunities, acquisition of skills and employment opportunities. This is because they are excluded in higher paying industries, managerial positions, and in entrepreneurial endeavours, and this implies that human capital is still not being utilised and thus failing to support innovations, competitiveness, as well as overall economic dynamism.

Besides, women unpaid caring work, which cannot be measured in official financial statistics, makes a huge difference in the economy. According to what was stated earlier, this invisible labour is estimated to add about 22.7 lakh crores in a year amounting to around 7.5 percent of the India GDP. The recognition of this number and its consideration as a part of national accounts would change the image of female economic importance like it would never change.

Women Empowerment Worth in India isn’t Recognized

The fact that such work is not recognized translates to the inability to consider the magnitude of the subsidy that comes with the unpaid labour that women offer in policies concerning social protection, provision of public services and development infrastructures. This results in insufficient investment in aspects that can back women up like childcare, eldercare, and the community health service thus continuing to burden them and delude them on their chances of taking jobs that pay them.

All these factors coupled up together, the demographic deficiency, the relative invisibility of unpaid labour activity, the discrepancies of employment statistics and the structural drawbacks, form a misleading description of economic situation in India. Ignoring the so-called missing millions and their real and potential contribution India is not only condoning gender inequality and failing to acquire a huge economic dividend. More detailed and accurate data system combined with specific policy intervention is necessary to allow unlocking this potential and providing inclusive growth to guarantee that an economic story is not just about one sector of the population.

Conclusion

The invisible nature of women and girls in the official statistics of India forms a deep-rooted institutional lapse with wide-scale demographic, social, economic repercussions. Whether it is the cold hard figures of lost women of 63 million people, and lost girls of 21 million that cannot be accepted in any social structure, where girls are given away under the title of unwanted to die as a result of deep-patterned gender Bias and sex-selective practices, or the undocumented feminine support of unpaid labour that supports societies, the projected picture is always short of an actual representation of their lives and their role.

The missing information on formal employment also vesils their plight as hidden in the informal sector together with the prevalence of demand-side discrimination in a way that they have not fully participated due to the structural hindrances that are tied to the norms of patriarchy, safety issues, and shortage of resources.

Further Reading

Drèze, J. and Sen, A. (1995) India: economic development and social opportunity Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Filmer, D., King, E.M. and Pritchett, L. (1997) Gender disparity in South Asia: comparisons between and within countries Washington, DC: World Bank.

Raju, S., Atkins, P.J., Kumar, N. and Townsend, J.G. (1999) An atlas of women and men in India New Delhi: Kali For Women.

Shiva Kumar, A.K. (1996) UNDP’s Gender-Related Development Index: a computation for Indian states, Economic and Political Weekly 31, 14, 887-895.